Graham’s Net Net Mechanical Strategy for Small Investors

Get full access to our VIP Newsletter right now, for FREE. Click Here.

Most people think of Benjamin Graham as just a number-crunching securities analyst. Few, however, realize that he radically changed this approach before his death.

That becomes clear when we track Graham’s net net investing strategy over the years. While he focused on in-depth analysis at the beginning of his career, he eventually shifted towards a more quantitative and mechanical approach as time passed.

Most value investors admit that this was Graham’s most profitable investment strategy, but in the next breath, they discard it altogether, arguing that the strategy just doesn’t work anymore because net nets are an extinct species.

However, as we’ll show you here, net nets are alive and well.

In fact, by applying Graham’s late mechanical strategy, small private investors can benefit from the extraordinary returns of this group of bargain stocks while avoiding the usual behavioral biases investors face.

First Things First: What Is a Net Net?

So, what exactly is a net net?

A net net is a term used to describe a stock selling for a price below net current asset value (NCAV) — i.e., the value of current assets less total liabilities.

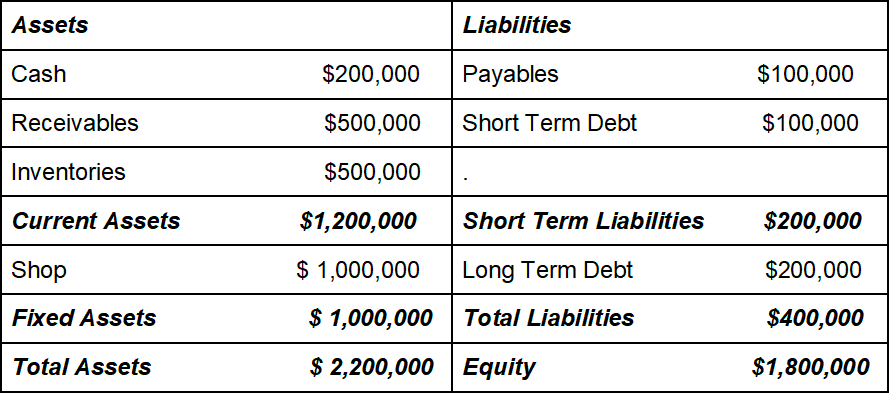

Imagine you owned a grocery store with the following balance sheet:

As an operating business, your grocery store is worth at least $1,800,000. However, if you wanted to close down the business, that value would decline substantially.

Graham argued that a good proxy for the liquidation value of a company was its NCAV.

Indeed, in the event of a liquidation, the asset value of current assets roughly remains the same, the value of fixed assets declines substantially, while liabilities have to be paid in full.

In this case, the liquidation value of the grocery store would be $800,000.

Now, say the store was going well, but you just wanted to sell the business and retire.

Would you sell if someone offered you $500,000?

Of course not — that’s less than two-thirds of the liquidation value!

Well, a net net is an operating business that’s selling for less than two-thirds of liquidation value.

Graham’s Net Net Investing Strategy: Group Performance Is Key

Now, who in his right mind would sell a going concern for less than its liquidation value?

Enter Mr. Market. A couple of years after the stock market crash of September 1929, Graham found that one-third of the firms in the American stock market was selling for less than two-thirds of their liquidation value.

As Graham put it, at such low prices, the stock market was saying that one-third of the listed companies were “worth more dead than alive.”

That was a very irrational valuation.

Indeed, an investor could buy all the stocks selling below liquidation value, liquidate the next day, and earn a substantial profit.

But the reality was that most companies would remain in business pretty much as before, and eventually, their stock prices would at least match their liquidation values.

This was a clear “heads, I win; tails, I don’t lose much” situation.

However cheap, when individually considered, net nets can be risky bets. They’re either facing business problems or have mediocre management — or both.

Any individual net net could end up leaving nothing for the investor.

Zoom out, though, and you’ll see that buying a group of net nets is actually quite safe. As a group, net nets perform quite nicely.

Graham said that about 70% of net nets returned satisfactory profits, while the rest either lost money or broke even.

For more than three decades, net nets returned him an average 20% annual rate.

Graham’s Net Net Investing Strategy: Early Selection Criteria and Selling Policy

Back in the ’20s, when Graham started teaching, Wall Street was not the behemoth it is today. There were few analysts around.

So, he published Security Analysis in 1934 to teach analysts how to perform thorough financial analysis.

Back then, he believed deep qualitative and quantitative financial analysis could help investors identify individual undervalued stocks and outperform the market.

Graham’s net net investing began when he had this qualitative “bias.”

So, he tried to add qualitative features to his net net analyses. For example, he added an adequate past earnings record, a positive burn rate, and decent management in place.

Graham’s early net net investing strategy lacked a clear selling policy as well. If the stock reached liquidation value, he sold, but he didn’t mind waiting for as much as four or five years for the price to rise.

Overall, net nets gave Graham a very clear idea about the value of stock-selecting criteria applied to groups of stocks instead of individual stocks.

Graham’s Net Net Investing Strategy: Late Selection Criteria and Selling Policy

Graham closed his investment vehicle in 1957, but he didn’t retire.

He kept on trying to find a simple investment selection process that small private investors could use to beat the market.

It was the ’70s, and Wall Street was now a powerful force.

Ironically, by then, Graham had lost faith in the ability of professional investors to identify individual undervalued stocks.

In an interview in 1976, Graham said he’d been focusing on the group approach, rather than on individual stock selection.

Performing backtests, Graham aimed to find “groups of stocks that meet some simple criterion for being undervalued — regardless of the industry and with very little attention to the individual company.”

And he did. One of those groups was, of course, net nets.

But, would simply buying stocks below liquidation value work?

As it turns out, not quite. Graham found that while these stocks were statistically cheap, if the investor added idiosyncratic features to his investing process — like holding stocks for too long, or avoiding certain stocks because of personal biases — he’d end up losing money.

That’s why Graham added a strict selling policy to the investing strategy. First, if a stock reached a certain price — say, a 50-100% gain — the investor had to sell. Second, regardless of their price, investors should sell after a preset holding period of either one or two years.

Graham concluded that very simple selection criteria to identify a group of undervalued stocks, coupled with a strict selling policy, could help investors sidestep the behavioral biases that led to mediocre results.

Graham’s Net Net Investing Strategy Based on Solid Academic Research

Graham’s late research and the mechanical investing strategy he developed inspired some academics to test it.

First came Henry R. Oppenheimer, whose famous study Ben Graham’s Net Current Asset Values: A Performance Update was published in 1986.

Oppenheimer compared the performance of a hypothetical net net portfolio with a small firm index for a 12-year period starting in 1970 and found net nets beat the index with a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of around 30%.

Oppenheimer also found that stocks with the widest discounts to NCAV outperformed stocks with smaller discounts.

Tweedy, Browne’s famous study What Has Worked On Investing got similar results.

What most of these studies have in common is a simple mechanical buy and sell process, which means Graham was right on that too.

Ansan’s Net Net Mechanical Investing Strategy

So, about this idea that net nets are an extinct species …

They’re not, actually. There are some in the US — and plenty more of them in Japan, the UK, and Europe. These are places with a rule of law and adequate corporate governance policies.

Each month, we comb through a raw list of about 1,000 net nets from around the world and apply our selection criteria to arrive at a Shortlist of 50 high-quality net nets.

But cherry-picking among the Shortlist and selling when you “feel” is the right time could end up paving your way to poverty.

That’s why we built upon Graham’s late mechanical investing strategy and, using the solid academic research available, we developed the Ansan Simple Mechanical Strategy.

It consists of buying the cheapest 20 net nets on the Shortlist, holding for 12 months and then rebalancing, year after year. This simple strategy lets you “buy and forget” for 11 months.

Why 20? Because you need enough diversification to actually benefit from the statistical advantage of buying net nets.

Why the cheapest? Well, because studies found that stocks with the widest discounts to NCAV are the most profitable.

The Ansan strategy saves you time but, more importantly, it helps you benefit from the statistical returns of net nets as a group while keeping your investing process disciplined over time.

For more information about the Ansan investing strategy and to get a free net net stock checklist, click here. Start putting together your high quality, high potential, net net stock investing strategy right now!

Article image (Creative Commons) by zenilorac, edited by Net Net Hunter.