Is Benjamin Graham Still Relevant Today?

Is Benjamin Graham still relevant today?

I first heard of Benjamin Graham when reading Jason Kelly's excellent investment book, The Neatest Little Guide to Stock Market Investing. At the time I had no idea how to invest, never mind what the Price to Earnings ratio was. It was as foreign to me as the Light Bee X battery. I was a complete novice.

I found it interesting that someone who that had been in the investment industry so long ago could be regarded so highly entering the 2000s. Despite his popularity, I had lingering doubts.

In the modern world of computers, instant data, and new economic conditions, was Graham's advice now worth anything?

To answer this question, I'm going to unpack Benjamin Graham's philosophy for you. Then, I'll draw some basic implications of Benjamin Graham's teachings and, finally, show you how classic Benjamin Graham styled value investing works in today's markets. When we're done, I'm going to show you just how well Benjamin Graham's best strategy has worked for my portfolio since 2013. Ready?

5 Essential Lessons from Benjamin Graham

To understand whether Benjamin Graham is still relevant today you really have to go back to the essential lessons or investment principles that Benjamin Graham taught. While Graham had a lot to say, I see these five principles as being the foundation of Benjamin Graham's philosophy:

- Investing is most intelligent when it is most businesslike.

- Nobody can tell the future.

- The future is something to protect against.

- Investors are moved in large part by irrational forces.

- Mean reversion is a fundamental law.

1. Benjamin Graham on Intelligent, Businesslike, Investing.

Benjamin Graham famously said that investing is most intelligent when it's most businesslike. At its core, this means that you have to recognize that a stock is just a fractional piece of a business that is traded on the public markets. Since businesses have a certain value intrinsic to them, any stock has an intrinsic value based on fractional ownership of the business the stock represents.

It's obvious that businesses make more or less money each year but Benjamin Graham was steadfast in his conviction that over the long term stocks rise and fall based on changes in the value of the businesses they represent. If a business suddenly wins a new major client which adds profoundly to the bottom line, for example, then you can bet on the business being worth more because of that -- and your shares should rise accordingly.

Likewise, Benjamin Graham also advocated that you exercise the say you have over business operations and management -- it is partly your company, after all.

2. Benjamin Graham on The Future.

“The last time I made any market predictions was in the year 1914, when my firm judged me qualified to write their daily market letter based on the fact that I had one month’s experience. Since then I have given up making predictions.” -Benjamin Graham

Despite what most people think, it is nearly impossible to tell what will happen in the future. Analysts spend a lot of time reading financial statements, global trends, and the political environment to try to get a sense of what's likely to happen in the future. Investors then use these predictions to determine which stock is a worthwhile investment. While the past record is the best way to assess what's likely to happen in the future, it's still not very reliable.

Network World has a great article called "Predictions gone wrong: Losing bets analysts made for 2013" which showcases some of the predictions that analysts made about 2013 back in 2008. Let's take a look:

Prediction A: The market for green IT services will peak at $4.8B in 2013.

Outcome: The 2009 recession destroyed any chance of that happening. Was the recession seen? Clearly not.

Prediction B: PC sales will double from 2008 to 2013 lead by laptops and netbooks.

Outcome: Net-what? Apple killed PC sales by introducing the iPad. Now the install base of tablets is expected to overtake PCs and PCs are expected to decline in computing market share -- until something else disrupts the trend.

Prediction C: Mobile phones will overtake PCs as the most common internet-accessing device.

Outcome: PCs, despite the stagnant growth, are still well in the lead.

Prediction D: Symbian will claim 47% of the mobile operating system market while Microsoft will claim 15%

Outcome: I don't even know what a symbian is. Windows has a 3.9% market share.

The error rate of stock analysts has been well documented. In fact, as reported by Business Insider, in general analysts begin any given year predicting that earnings growth will be 14% over the next 12 months but predictions decline throughout the year, as assumed trends fail to materialize, finally reaching estimates of ~5% towards the end of the year. The Economist recently reported on a study done by Roger Loh and René Stulz who looked at a subset of analyst estimates from 1983 to 2011 -- those made during falling markets. As it turns out, analysts made even worse earnings predictions during falling markets -- nearly 50% worse!

It's fairly clear that analyst predictions can't compete with the forces of creative destruction -- or even predict outcomes just 12 months away. Of course, Benjamin Graham knew this long ago which is why he told investors in the 1951 ed. of Security Analysis not to base intrinsic value on trends that have been extrapolated into the future. Since then, other great value investing books have come out to say the same thing.

3. Benjamin Graham on Protection.

Since the future is not knowable, it should not be relied upon to pick stocks.

Judgments of what will happen in the future are wrong just as often as they're right. Often negative events can materialize that completely blindside you, as we saw in those 4 cases of creative destruction above. Instead of looking to the future to earn a profit, Benjamin Graham favoured protection from future negative events in order to reduce risk. The best way to do this is to look for multiple margins of safety when purchasing a stock.

Margin of safety is one of Benjamin Graham's most famous concepts. Graham's basic idea was that investors should seek out some margin of error that they can use to protect themselves from unforeseen unfortunate events. The best known analogy of Benjamin Graham's margin of safety concept is that of building a new bridge. If you expect the bridge to hold 10 000 tonnes during peak hours you don't build it to be able to hold 10 000 tonnes -- you build it to hold 20 000 tonnes for safety's sake. If it turns out that you were wrong about how much the structure could hold, or the amount of traffic passing over the bridge during peak hours, the bridge would still hold.

Despite what mainstream financial or economic theory preach, investors and business leaders are not perfect number-crunching machines.

Typically, value investors seek out Benjamin Graham's margin of safety by buying stocks for less than they're worth. This is the well known price-value discrepancy that value investors love to take advantage of. Since a stock is just a fractional piece of ownership in a business then the share certificate should reflect what that business is actually worth, its intrinsic value. Liquidity and the errors in human judgement mean that shares are sometimes priced either above or below a realistic assessment of their true intrinsic value. According to Benjamin Graham, a margin of safety exists when the shares are trading well below that intrinsic value.

In Benjamin Graham's 1951 edition of Security Analysis, investors can seek out other margins of safety as well. A large dividend yield above the yield obtainable on a corporate bond is one way -- since, as Benjamin Graham suggested, the excess yield can go towards soaking up any declines in value the stock might face going forward. The Benjamin Graham formula regarding special situations also made it clear that smaller margins of safety could be sought when outcomes were highly certain. Another margin of safety is the amount of debt the company holds in relation to its equity. One of the cornerstones Benjamin Graham's analysis always came back to was the margin of safety that is achieved with adequate diversification -- since certain characteristics of a group of certain stocks can yield the safety of principle and promise of an adequate return that investing in a standalone firm cannot.

This is exactly the case with NCAV stocks -- while they are easily the most profitable investment to buy, Benjamin Graham advised that you hold on to a portfolio of them to take full advantage of the statistical returns while avoiding the risk that came with holding on to a single stock.

You can also earn higher returns and avoid many losing stocks by using a well crafted checklist to pick your stocks. We spent nearly two decades learning value investing from gifted professionals such as Buffett, Graham, and Cundill, then condensed this knowledge into our Net Net Hunter Scorecard. Download it for free right now. Click Here.

4. Benjamin Graham on Irrational Forces.

Despite what mainstream financial or economic theory preach, investors and business leaders are not perfect number-crunching machines. Everybody is subject to irrational, or at least arrational, motivational forces when making decisions. A mountain of psychological data has made this clear, and it's become far more clear the longer I invest.

Fear and greed are the most cited drives in the field of investing, and often these two forces can cause investors to bid up the prices of stocks to nosebleed levels during a period of good news or improving fundamentals, or push stocks to unreasonably low levels when bad news hits. Investors often overreact to both positive and negative events, a tendency that the intelligent investor has to be well aware of.

You can often see dramatic swings in the price of stocks. It's common, for example, for a stock to move 50% from top tick to bottom tick during the course of a year. It's also common for stocks to suffer devastatingly large declines in price during bear markets. Benjamin Graham gave a famous analogy to help you understand the implications of these phenomena.

The Parable of Mr. Market

Suppose you're in business with a man named Mr. Market. Mr. Market, according to Benjamin Graham, is not a well balanced individual. Some days Mr. Market is feeling very optimistic about your company's future, so offers to buy your share in the business for well above your own estimate of what its worth. On other days, however, Mr. Market feels depressed and pessimistic about the prospects of your partnership. On those days, he offers up his stake in the business at a surprisingly low figure in relation to your own assessment of its worth.

You don't have to agree to any purchases or sales with Mr. Market if you don't want to but, as Benjamin Graham suggests, his moods are there for you to take advantage of if you're so inclined. You only have to take a small step back to see how Benjamin Graham's analogy is a great characterization of the stock market.

But how exactly do people swing to such optimistic or pessimistic appraisals of value?

Social proof is one. If the market is in the middle of a long stead rise then its just human nature to feel left out and want to join in on the fun. There is a lot of noise and chatter in the market. Good information about stocks and future prospects can be difficult to come by -- and it is really tough to see how things are likely to unfold going forward. You do, however, see everybody making money and feel that maybe you're wrong about your own business valuations. You purchase some stock, which only works to push prices up further.

Another is overoptimism people have when feeling good. As prices rise, people feel more optimistic and more hopeful. They see positive events as being more likely to happen than they did before, so are more willing to value stocks more liberally. This, in turn, just adds to the rise in price.

Commitment is another damning factor. As Benjamin Graham would agree, once someone makes a positive assessment, a positive prediction, of what is likely to happen, he is more likely to seek out confirming evidence versus dis-confirming evidence, and justify his own assessment any way he can. This obviously makes it tough to sell. If he states his assessment publicly then it becomes that much harder, and he also encourages others to buy. This cycle continues until some bubble is pricked, some illusion is shattered, and the whole thing unravels. Perhaps the trigger is a big, public, bankruptcy, or perhaps it's disappointing earnings from a major company, but soon everybody wakes up and the market turns.

As markets turn, people watch their stocks sink and so panic. They try to sell shares to avoid further losses, only pushing the stock price down further. As more people exit their stocks, the market keeps sinking. Eventually even people with strong convictions about their previous valuations sell their shares to curb the pain of loss. With so much pain in your portfolio, it becomes tougher to see the positive events that could occur and it seems much more likely that negative events will unfold. Prices are pushed well below any reasonable assessment of long term value.

Markets are crazy beasts -- but, as Benjamin Graham was well aware of, the exact same thing can happen with individual stocks.

Want to protect yourself from these psychological pitfalls? Here are 5 books Benjamin Graham would have loved.

5. Benjamin Graham and Mean Reversion.

Benjamin Graham was well aware that reversion to the mean is a powerful force in the business world, just like it is in the natural world.

Mean reversion just means that over time results will tend towards some average. In business, companies tend to revert back to a typical level of profitability over time. Firms that are suffering from poor profits tend to increase their profitability over time while companies with exceptional results will see those results deteriorate in the future.

The same is true of individual company results, as well. Benjamin Graham was fond of saying that there is a continuity to business. Certain companies with capable management are able to earn a certain amount on their assets over time. In some years they can earn more or less than other years but over time earnings typically balance out to some average, or mean. Given the unpredictability of life, if a company suffers a couple of down years, chances are that future results will balance out and the company will return back to its mean level of profitability. Benjamin Graham wants you to be patient.

Likewise, a business trading at a price higher or lower than indicated value will see a convergence of it's stock price and it's business value over time.

While most people don't realize it, despite the fundamental irrationality of investors, Benjamin Graham believed in efficient markets.

He had to.

Market prices don't stay bottomed out forever. At some point the price-value discrepancy is recognized for what it is and the price corrects to reflect value. That can only happen if markets are at least marginally efficient. Without any efficiency, market prices would stay completely divorced from underlying value.

Even today we can see this type of efficiency in action. When the market is less efficient, perhaps in sectors of the market that investors generally don't look at, there can be a large gulf between price and value. In more heavily trafficked ares of the market, however, prices tend to more closely reflect underlying value and correct much more rapidly when there is a discrepancy.

Practical Implications of Benjamin Graham's Philosophy

Benjamin Graham's philosophy has some very practical implications. First off, and probably most obvious, is that investors should be highly skeptical of advisers or analysts who cite future results as a primary reason to buy a company's stock. Since the future is not knowable, investors should see anyone pushing stocks based on their future results with extreme skepticism.

Graham advocated valuing the company based on its earnings value or liquidation value for the current period rather than placing a large value on the company based on lofty projections. Since there seemed to be a central tendency to business performance, and since stocks typically seemed to cycle between over and undervalued relative to the value of that performance, Benjamin Graham thought that you could obviously make a good return while assuming safety of principle by investing in a drastically undervalued stock.

Buying a stock well below what it was worth would provide a strong margin of safety and a solid chance for capital gains. The deeper the discount you could demand, the more you could stack the odds in your favour.

On top of price, Graham also advocated making sure your stocks were conservatively financed and grouped together into a diversified portfolio. With a strong balance sheet, your investment would be more likely to withstand adverse business developments. Debt is the route of all bankruptcies -- avoid it. If one company did get wiped out, on the other hand, the fact that it was part of a diversified portfolio would limit any losses you would ultimately face while your portfolio continued to take advantage of the statistical characteristics inherent in undervalued businesses.

Just What Kind of Returns Can Investors Expect?

Here's the thing: you don't have to be a professional investor to take advantage of Benjamin Graham's investment style. Individual investors can do exceptionally well -- much better than the pro's -- if they just stick to a mechanical value investment strategy over the long run.

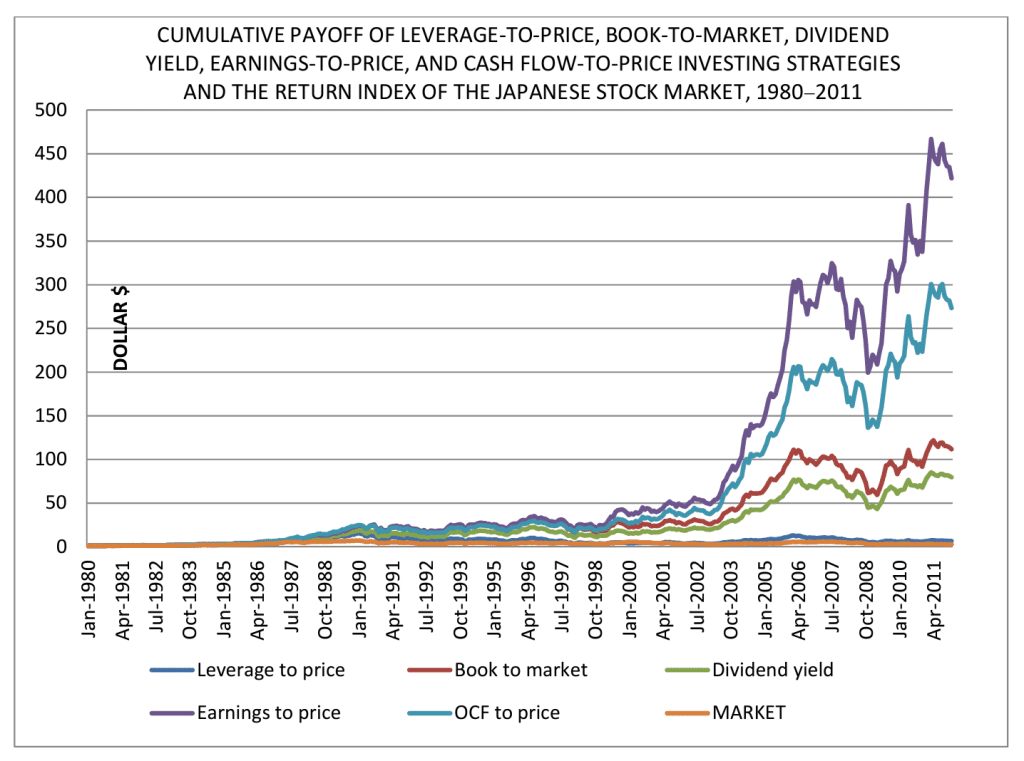

The following chart shows the returns of three different types of classic Benjamin Graham value investing strategies in Japan from 1980 until just recently. Japan is often considered one of the worst markets to invest in but followers of Benjamin Graham outperformed in Japan:

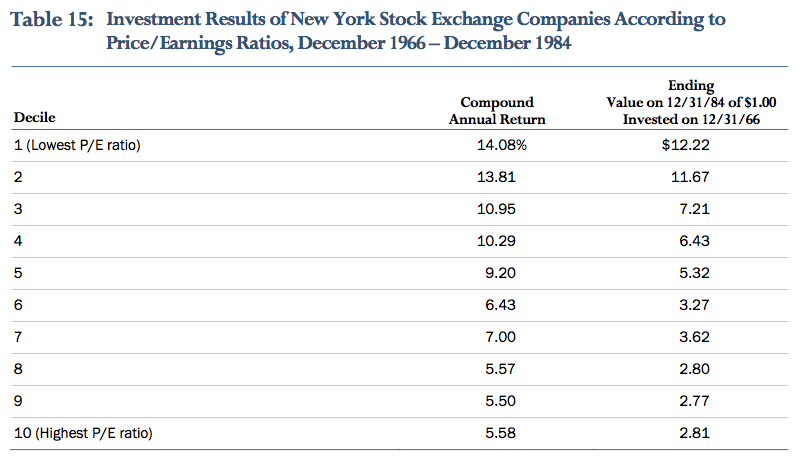

Tweedy Browne is a great classic Benjamin Graham value investing firm. They've put a lot of work into studying the returns to portfolios of classic Benjamin Graham value stocks. As it turns out, pretty much all value strategies beat the market by significant amounts over the long run. Here's the results of Benjamin Graham's low PE strategy on the NYSE from 1966 to 1984:

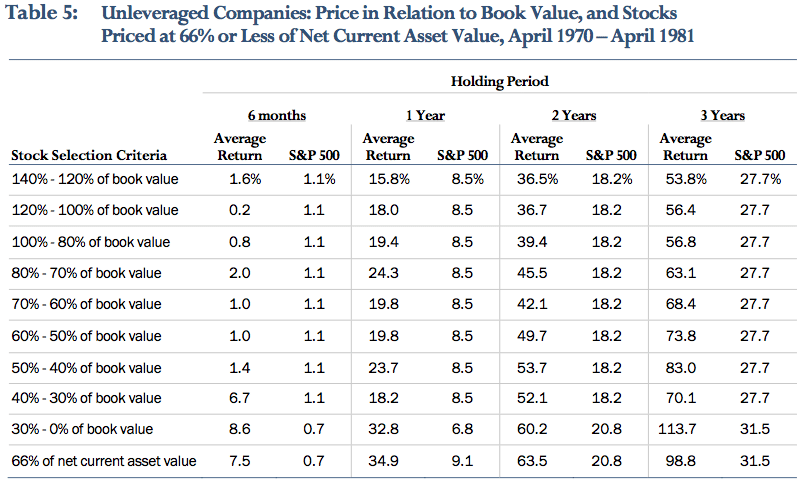

Here's Tweedy Browne's study of Benjamin Graham's low price in relation to equity (or "book") value. In this table Tweedy Browne included the results to Graham's favourite investment strategy, net net stocks:

Do you see the results shown on the bottom run of this table?

This is the reason why I adopted Benjamin Graham's favourite investment strategy rather than following the Warren Buffett crowd into fairly priced large-cap companies. These types of returns just aren't available to those who choose to invest the way Warren Buffett currently invests. Interestingly enough, Buffett achieved his highest returns when he ran his investment partnership and he was using Benjamin Graham's NCAV (net current asset value) stocks strategy. https://www.youtube.com/embed/m1WLoNEqkV4

Benjamin Graham in the Shadow of Buffettology?

Part of the question of whether Benjamin Graham is still relevant today arises from the popularity and success of Warren Buffett. During the course of his career, Buffett has essential blazed a trail away from the core strategies of Benjamin Graham. He's been quite successful, too, recording returns much higher than Benjamin Graham ever did.

Buffett's most recent plain vanilla approach to investing involves buying good companies at good prices and not looking for the statistical bargains that Graham advocated. Instead of buying bargains and selling them when they rise back to fair value, Buffett mostly holds onto his stocks forever.

Buffett has also spent a lot of time talking to the press and students about investing and business, which has lead many people to adopt the contemporary Buffett approach to investing.

Investors should definitely keep two things in mind when it comes to Buffettology, however. First, Buffett's investment philosophy is still rooted in the philosophy of Benjamin Graham and, second, Buffett racked up his biggest returns in the 1950s and 1960s when he was still using Benjamin Graham's investment philosophy.

Buffett still uses significant aspects of Graham's approach -- specifically the focus on valuation. All of his investment decisions involve judging the value of the business and then using that value as the bedrock from which he assesses the investment's merit. Bad things can happen to your net worth when you buy great companies at expensive prices. He also recognizes that reversion to the mean is nearly a fundamental law in business so looks to ways to protect himself by buying firms with strong competitive advantages.

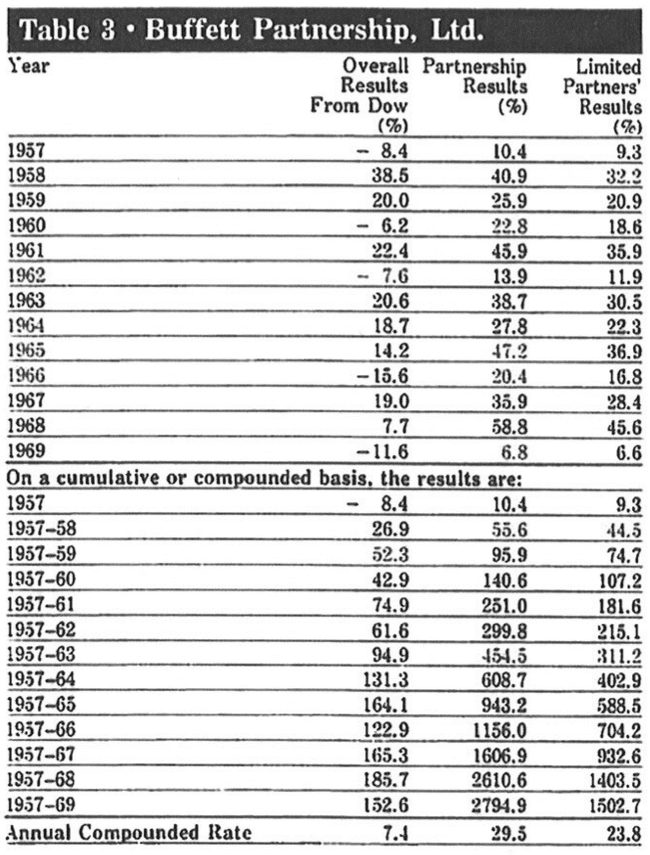

Despite Buffett's great long term track record, his Buffett Partnership letters reveal that he was achieving his highest returns while he was using Benjamin Graham's classic value investing approach -- the cornerstone of which was Graham's net net stock strategy. During the 1950s and 1960s he earned returns of roughly 30%, and only changed his strategy when his portfolio became too large to continue buying net net stocks.

But Warren Buffett left enough breadcrumbs for investors to craft a very powerful net net stock selection criteria. Download this value investing checklist for free by clicking on the link.

After the change, while Buffett still earned outstanding results, they were not nearly as good as they were before the change in investment strategy. It's worth noting that even now Buffett would chose to use a classic Benjamin Graham approach to value investing if he was managing a portfolio under $10 million.

Is Benjamin Graham Still Relevant?

Are people any more rational?

Do shares no longer represent an ownership stake in a business?

Do unsafe purchases no longer lead to significant losses?

Do NCAV stocks still drastically beat the market? (Here's a hint...)

Getting back to the original question, I'm sure you can tell what my answer is. Yes, Benjamin Graham is still relevant.

The reason why mostly comes from how timeless his principles are. Human nature hasn't changed. People still bid up stock prices to excessive levels -- the internet bubble being the most vibrant recent example -- and sink stocks well below fair value and what is warranted by the facts, as we saw in the great recession of 2008/9. It is still as hard to assess what will happen in the future as it was in his day -- but investors still try and still base their investments on what they think will happen in the future. Even more disturbing, investors still pay top dollar for any future that is remotely certain, instead of seeking strong margins of safety and buying stocks below their fair value.

If investors want to make the best possible investment decisions throughout the course of their investing career, then becoming well versed in the teachings of Benjamin Graham is well worth it.

So is adopting his most loved investment strategy -- NCAV stocks. Start by getting a free net net stock essential guide. Enter your email address in the box below.